Guest post by Martin Mercier, P. Eng, is Strategic Marketing Manager for IoT and Connected Systems, Cooper Lighting Solutions, a Signify business (CooperLighting.com).

Emergency lighting has one job: keep people moving safely when normal power fails. Put simply, it is the system that keeps a safe level of illumination—and power for lighting-related critical equipment—when normal power fails so people can get out safely. What makes it different is that it’s a life-safety system: decisions can’t be driven only by cost or convenience, and in some applications the right solution may be pricier than ambient lighting—though, as we’ll see, new technology can actually lower cost while improving emergency light quality. Also, its compliance is performance-based, not product-based: as such, an UL mark alone doesn’t guarantee it was used in a well-designed project or used in the right application; the system tested on site must prove required performance, as designed recommendations per building codes, including the expected maintained illumination for a certain minimum of time.

Emergency lighting has one job: keep people moving safely when normal power fails. Put simply, it is the system that keeps a safe level of illumination—and power for lighting-related critical equipment—when normal power fails so people can get out safely. What makes it different is that it’s a life-safety system: decisions can’t be driven only by cost or convenience, and in some applications the right solution may be pricier than ambient lighting—though, as we’ll see, new technology can actually lower cost while improving emergency light quality. Also, its compliance is performance-based, not product-based: as such, an UL mark alone doesn’t guarantee it was used in a well-designed project or used in the right application; the system tested on site must prove required performance, as designed recommendations per building codes, including the expected maintained illumination for a certain minimum of time.

As we will see, as for using lighting controls to provide the right emergency lighting at the appropriate time, the building codes themselves are largely technology-neutral, which is why controlled (including wireless) solutions are viable, as long as they meet the performance requirements, as any system needs to do as well.

We’re discussing this more recently because advances in lighting controls and energy management have made code compliance more complex—but also opened up better options, with higher-quality emergency lighting, easier testing, maintenance, and simpler design and installation efforts.

Terms used in this article

• AHJ — Authority Having Jurisdiction (the officials who approve your installation).

• ELCD/ALCR — UL 924 devices that force luminaires to emergency output.

• DCEL — UL-listed luminaires with a dedicated emergency input.

• BCELTS — UL 1008 branch-circuit transfer switch.

• EPSS — generator/inverter system providing emergency power.

When did it all start?

Did you know it all started with too many standards for sprinklers’ piping size and spacing back in 1895?

Did you know it all started with too many standards for sprinklers’ piping size and spacing back in 1895?

Yes, in the early work just before the NFPA, there were some insurers and engineers who united to recommend uniform sprinkler sizes and spaces (which became NFPA 13). The NFPA was founded in 1896 to bring uniformity to fire protection. One year later, the first National Electrical Code (NEC) set common safety rules for wiring; shortly after, by 1911, the NFPA had taken over sponsorship of the NEC and has maintained it ever since. On the life-safety side, NFPA’s Committee on Safety to Life published the 1927 Building Exits Code after studying deadly fires; that lineage evolved into NFPA 101 Life Safety Code.

Today’s emergency lighting traces back to the 1927 Building Exits Code—that at its source is occupants shouldn’t be in the dark and its DNA is still intact a century later, with performance-based requirements and technology-neutral standards. That’s why modern, wireless-assisted emergency lighting can comply: the codes care that people can see and exit safely, not which wire (or radio) told the lights to come On.

What the code actually asks for

Think of it in three layers. Take a deep breath… and here we go!

Think of it in three layers. Take a deep breath… and here we go!

First, the building codes (NEC/NFPA 70 Article 700 et al) govern power sources, transfer, separation/identification of emergency circuits, testing, and documentation. Or what it comes down to… Across adoptions of NFPA 101 and the IBC, designers must provide along the means of egress an initial 1 fc average (≥0.1 fc minimum) at the floor, allowed to decay to 0.6/0.06 fc by 90 minutes, with uniformity ≤40:1. Stairs carry a 10 fc requirement in normal operation. These values are technology-neutral: The code doesn’t mandate how you get there—only that you do and that the system behaves automatically on power loss. Article 700.24 clarifies directly controlled emergency luminaires vs. bypass/force-on methods; Article 700.11 sets rules for Class-2 emergency circuit identification, separation, and protection.

The initial 1 fc average (≥0.1 fc minimum) at the floor, allowed to decay to 0.6/0.06 fc by 90 minutes, with uniformity ≤ 40:1 is what you have to remember to look smart in a egress coffree corner conversation, for most of it.

Knowing that we have design guidance per safety codes, do you feel safer now? If you do… you shouldn’t! What about the products to be used? How do we know they were designed to support such requirements and in a sustainable way?

Here comes UL!

This is when product standards come in and govern what the equipment is listed to do.

This is when product standards come in and govern what the equipment is listed to do.

UL 924 — Emergency lighting & power equipment: exit signs, unit equipment, micro- and central inverters, and Emergency Lighting Control Devices (ELCD/ALCR) that force luminaires to the emergency state. It also covers Directly Controlled Emergency Luminaires (DCEL) that accept a dedicated emergency input.

UL 1008 — Transfer switch equipment, including branch-circuit emergency lighting transfer switches (BCELTS).

Field rule: If you’re changing sources, that’s UL 1008. If you’re overriding control/forcing full output, that’s UL 924. We won’t address UL 1008 here since not directly related to lighting equipment.

Do you feel safer knowing we have design guides and certified products? NO, not yet! Remember I said early performance driven… Then how we validate it?

Boom. Authority Having Jurisdiction

It is with the AHJ or Authorities Having Jurisdiction. Defined by NFPA as the organization or person that enforces the code or approves an installation, reviewing listings, the sequence of operations, and the test plan, then witnessing tests on site. The whole system needs to be evaluated as installed for that facility and accepted by the AHJ. The AHJ evaluates performance on site (including modern, even wireless, topologies where adopted); if approved, they enable a Certificate of Occupancy (CO), while non-compliance can trigger corrections or a provisional CO with deadlines. After opening, upkeep is mandatory: The 2026 NEC 700.4 adds Commissioning and Servicing—(B) Tested Periodically requires a testing schedule approved by the AHJ, and (D) Record Keeping requires written or digital records available to those who design, install, inspect, maintain, and operate the system (a digital log makes this far easier). In parallel, 2024 NFPA 101 §7.9.3 requires periodic testing of emergency lighting equipment.

Who plays AHJ? For example, in New York City it’s the Department of Buildings (DOB) with FDNY inspectors; in Canada it’s typically the municipal building official (often alongside the provincial electrical authority).

How does it happen in reality, or what are the typical solutions?

As a start, we can separate different solutions into 4 categories.

Centralized vs. distributed

Centralized vs. distributed emergency lighting boils down to where the backup power lives and how it reaches the luminaires.

In a centralized approach, a generator or central lighting inverter (EPSS) feeds selected circuits so the normal luminaires ride through an outage—great for large corridors and open areas, fewer batteries to service, and clean ceilings, but it can mean heavier upfront infrastructure and careful circuiting.

In a distributed approach, backup power sits at the edge—unit equipment (bug-eyes/combos), LED emergency drivers inside fixtures, or micro-inverters per fixture/zone—ideal for retrofits and targeted wayfinding with minimal new conduit, but it spreads batteries and maintenance across the floor. Most modern designs blend both: centralized coverage for big spaces, distributed devices where wiring is hard, all coordinated by code-compliant controls (UL 924/UL 1008) to ensure maintained or normally-off paths meet 90-minute, illumination, and fail-safe requirements.

Maintained vs. non-maintained (why it matters with controls)

• Maintained (normally On): part of everyday lighting; must force to emergency when power is lost—even if the space was dimmed. Use ELCD/ALCR or DCEL.

• Non-maintained (normally Off): only energizes in an outage, typically via inverter/generator or local battery.

Show me how! Okay, now we review traditional and newer approaches for emergency lighting! (You made it here? Wow, now keep reading–this is the interesting part!)

• Unit equipment (bug-eyes/combos) and LED emergency drivers provide local battery back-up where circuits are hard to reach or you want targeted wayfinding light.

• LED emergency drivers provide local battery back-up where circuits are hard to reach or you want targeted wayfinding light.

• Central inverters / generator (EPSS) keep normal luminaires on during outages—great for large open areas and corridors, and to reduce battery proliferation.

• Micro-inverters (fixture/zone) deliver full-output ride-through with minimal rewiring.

• For controlled spaces, add UL 924 ELCD/ALCR (bypass/force-on) or specify DCEL luminaires so dimmed scenes cannot suppress the emergency state.

And now for the Control Dilemma

Can lighting controls used to enhance lighting quality and energy savings also play a role in emergency lighting? After all, this is a lighting control website, right?

In a lot of projects, lighting controls are required by energy codes to turn lights Off or dim them during normal operation. Yet emergency lighting must provide a reliable path of egress that those same controls cannot turn Off. How can two seemingly opposite requirements coexist—sometimes even within the same fixture?

Well, in May 2020 (effective May 2022), UL added Clause 29A to UL924 and tied it to the ELCD test sequence in 47.2(c) which states that if an Emergency Lighting Control Device (ELCD) provides control functions—On/Off/dim—it must continuously monitor the “normal-power present” signal for its controlled branch circuit. That monitoring can be wired or wireless, but it must remain functional independent of the emergency power feeding through the device. In other words, even while passing emergency current, the ELCD must still watch normal-power status and respond automatically and fail-safe.

This is the technical bridge that finally lets general lighting controls participate in emergency-lighting control. When implemented with UL-listed ELCDs or directly controlled emergency luminaires (DCELs), the same control infrastructure that dims, senses, and reports during everyday use can—upon loss of normal power—automatically shift into emergency mode, delivering required illumination while preserving code compliance. Why? Because the key factor is a system with a fail-safe behavior: the control system may add intelligence, but the UL-924 device guarantees that light comes On even if the regular power signal monitored by the control system disappears, or if the system overall disappears.

You aren’t hearing anymore from the lighting control on if there is regular power? You go emergency mode! Regardless of the reason.

No pre-set dimming anymore, nor end-user changing the light levels from a wall station, then.

Wait. Aren’t we trying to do the opposite per the latest Energy Building codes?

Yes, both building and energy codes are designed to co-exist: life safety wins in an emergency, and energy efficiency governs in normal operation. Most energy codes (Title 24/ASHRAE-IES 90.1/IECC) exclude emergency lighting that is normally Off from lighting power and control requirements, so dedicated EM fixtures aren’t penalized for being ready-but-Off. For maintained luminaires (used every day), you still meet energy rules—dimming, occupancy, daylighting—until normal power is lost; then a UL 924 override or directly controlled emergency input takes priority and drives the required emergency level for 90 minutes.

Here’s a summary of U.S. energy-code exceptions:

• ASHRAE/IES 90.1 excludes normally-Off emergency lighting from its lighting power and control scope;

• IECC 2021 likewise exempts 24-hour emergency/security lighting and emergency egress lighting that is normally Off; and

• California’s Title 24 allows up to 0.1 W/ft² of designated means-of-egress lighting to remain continuously On without the usual area/automatic shutoff controls.

Show me the money!

0-10V

0-10V system architecture example

DALI

As we know, DALI control systems are communicating on a low-voltage control bus to LED drivers and other control gear; for emergency, the power continuity still comes from your EPSS (generator/central inverter) or local batteries. In normal operation, DALI runs scenes, occupancy/daylight, and keeps DALI emergency devices (IEC 62386-202) on a schedule for self-test and status reporting.

When normal power is lost, two things happen: (1) the emergency power source keeps the designated circuits/luminaires energized, and (2) the emergency input/logic takes over—either a UL 924 interface forces maintained luminaires to the required output (bypassing dimming), or DALI emergency control gear inside the fixtures automatically switches to its emergency state at a defined level and logs the event. Because the EM behavior lives in the listed device, fixtures go to (and hold) the code-required output without relying on the central controller, while DALI still gives you grouping, test automation, and fault reporting to prove compliance.

Keep in mind that a DALI system when disconnected doesn’t fail to high as 0-10V. Also the Emergency Lighting scenes need to be programmed. Also self-contained emergency is included as part of DALI-2 certification. It typically includes support for function and duration tests next to drivers going into emergency mode upon mains power failure.

The DALI Alliance released to its members a new Part 254 that extends the emergency specifications with information on batteries. “Part 254 – Particular requirements for control gear – Extended emergency data (device type 53)”. Also not released yet or part of the certification program yet, but there is work done by the DALI Alliance around centrally supplied emergency lighting.

DMX512

Similar behavior can be achieved with DMX512 system–a good solution for theatrical lighting related applications such as theater or sports-related environments. DMX512 is a unidirectional show-control protocol that streams levels to fixtures; it doesn’t provide power continuity—that still comes from your EPSS (generator/central inverter) or local batteries. For egress lighting, you must make DMX fail-safe: insert a UL 924 emergency interface (or ELCD/ALCR) that, on loss of normal power or on an emergency contact, overrides DMX and drives designated channels/fixtures to the required emergency level (typically full). Don’t rely on a console or “hold last look/blackout” loss-of-signal behavior; instead, wire an emergency input from the EPSS/fire alarm/inverter to the UL 924 device or architectural DMX controller’s EM input so the scene changes automatically. Document which DMX universes/channels are egress, show that dimming is bypassed in EM mode, and keep the emergency circuits/luminaires energized by the listed source. If you use RDM/sACN for monitoring, treat it as supervision only—the listed UL 924 override is what satisfies the life-safety requirement.

How about wireless solutions?

The twist in 2025 is that we can often deliver those outcomes with far fewer new wires by pairing listed emergency devices with a wireless control/supervision layer. The result: faster retrofits, cleaner ceilings, and better testing/records—without compromising life safety.

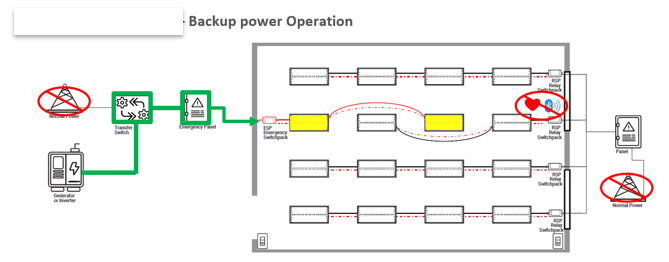

The diagram illustrates the full sequence of operation when normal AC power is interrupted. Under normal conditions, NPS devices broadcast that utility power is present and all fixtures operate in their normal, controlled mode. When normal power is lost, the automatic transfer switch (ATS) shifts to the emergency source within 3–5 seconds and, after two seconds of power loss, emergency luminaires on the ESP drive to full output. If no NPS signal is received for more than seven seconds, the ESP keeps those emergency fixtures at full brightness until normal AC power is restored. Once utility power returns, the ATS reconnects to the grid and the emergency fixtures quickly transition back to their previous, non-emergency lighting state.

The solution includes selected fixtures to be wired to the emergency power and deliver emergency lighting, and other selected fixtures providing the Normal Power Signal (NPS), sometimes referred to the heartbeat or beacon, to communicate that the regular power is present on site. Wireless is not your life-safety source; the emergency power source and any power transfer devices remain your hard-wired and listed source. The wireless solution, mostly a mesh network solution, needs to be designed with layers like critical plumbing: stagger broadcasts, avoid network-wide floods, and ensure each emergency device has a local fail-safe path that does not depend on receiving a packet at the worst moment. In other words, optimize to prioritize emergency beacon signals, versus traditional control commands such as manual switch dimming, daylighting override, or a scheduled dimming action for a specific zone. If the beacon signal isn’t prioritized and is not received by an ambient fixture acting as an emergency fixture, it will default to high or its emergency lighting pre-programmed level. Fail-safe, but unnecessary overrides on-site are to be avoided.

The mesh continually heartbeats the NPS beacon signal as defined by UL924 and seen earlier in the text; if heartbeats stop, emergency devices go to emergency light level output, something their full output or other planned leveler per minimum level requirements. Outside emergency lighting mode, an override command can be sent so luminaires go to the required emergency state on loss of normal power or control for testing, or site inspections.

The same system backbone can provide supervision & testing with an instant access to the status of your system and constantly monitor is status, and not only when scheduled for testing or inspection. It can automate and performs all required testing monthly 30-second and annual 90-minute tests, store digital logs and or email reports—a must for AHJ audits, with no searching for reports during an inspection. Also, no ladders, no pushing buttons, and no documentation; reports can be easily exported to prove the system status is 100%.

Conclusion

Emergency egress lighting isn’t about gadgets—it’s about outcomes: the right light, for long enough, every time.

The good news is that modern, technology-neutral codes let you pair proven life-safety hardware (UL 924/UL 1008) with smarter control layers—wireless meshes, DALI Emergency, 0–10V with inverter auto-dim, and even DMX with UL-924 overrides—to deliver better visibility, simpler installs, and automated testing/records.

If this article sparked ideas, take the next step: Pilot a small zone that blends your everyday controls with a listed emergency method, document the fail-safe sequence, and review it with your AHJ. Then scale what works—add self-test reporting, digital logs, and wireless supervision—to reduce OPEX while raising safety and light quality. Cut the cord where it helps, keep the code where it counts, and keep learning—because the fastest path to safer buildings is staying current on the tools that make compliance easier and outcomes better.